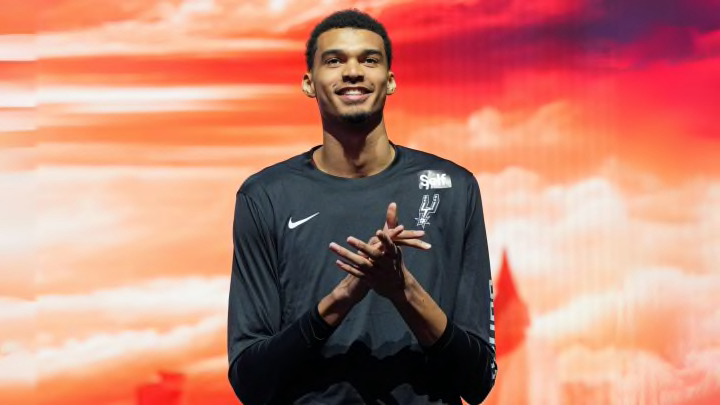

Long legs in stride, Victor Wembanyama made his way up the small steps of the makeshift stage taking up the key of the San Antonio Spurs’ home floor at Frost Bank Center.

It was his introductory press conference. He was coming straight from the riverwalk — with enough time to change into much more formal attire — and already fans were showering him with love. He had just finished high-fiving and shaking hands with the fans in attendance at the Spurs’ arena as every camera in the room was fixated on him.

He was going to have to get used to that.

As Wembanyama reached the top step, his outstretched arm was already long enough to shake the hand of his general manager. So, he did. And whether it was reaching for Brian Wright’s hand, showing his fans love or blocking shots, stretching his arm out was also something he’d have to grow accustomed to.

For the rest of the season, every time the rookie would emerge from the back tunnel, home or away, he’d be met with hands. Whether it was young fans or adults looking to get a good up-close video for their social media, he was always going to be the center of attention.

Wembanyama was well aware of that fact. The French phenom knew where everyone’s eyes would go as soon as he stepped into a room, but as his eyes scanned the arena floor that he’d play in 41 times that upcoming season as he took his seat, he didn’t even see the biggest spectacle on the stage.

Not at first, anyway.

Things look a lot different for Wembanyama now than they did when he was a teenager in France.

Back when he was growing up, it was clear that basketball was his goal. From watching Tony Parker and Boris Diaw — two other Spurs legends that paved the way for his home country to begin a long-lasting relationship with the San Antonio-based team — to growing to be nearly seven feet tall at 14-years-old, the Frenchman was destined to standout in a crowd.

But apart from his height, he wasn’t quite the superstar off of the court the way he is now. In fact, according to French journalist Benjamin Moubèche, passing him on the sidewalk was a normality.

“At the beginning, it was like that,” Moubèche said. “He was able to work in the streets, but as the season continued, everybody started to know who he was. I will say, (however) that he gained a new status by just coming to the NBA and being a star there.”

Moubèche had been following Wembanyama for an entire season before he made his way to San Antonio. He was there when the Spurs star faced off against now-Portland Trail Blazers rookie Scoot Henderson for the first time in a G League Showcase. He was there when the Frenchman nearly led his team to a championship before being swept in the best-of-five series.

And the biggest difference from then to now?

The amount of media availabilities.

Still wearing his game shorts and a white sleeveless undershirt, Wembanyama stepped up to the podium and sat down with a contemplative stare in his eyes after losing a franchise-worst 18 straight games. This particular time, it was at the hands of the LeBron-James-less Los Angeles Lakers.

The Spurs rookie took a look around and muttered one word: “Hey.”

Two days later, and the same player would sit down in the same chair in front of the same crowd and mutter the same word. That particular night, his team would be feeling the “addictive” effects of winning after knocking off the Lakers with James back on the floor.

Wembanyama would hide a grin before addressing the media — something he knew came with the job — and he’d be interrupted a few times by Keldon Johnson yelling and a loud speaker blaring music. That night, he’d be a winner. But this night was not that one. Tonight, he was a loser.

As he was queried about the game and his team’s loss to Los Angeles, his answers were as straightforward as the questions being asked. There wasn’t much of a story to be told other than the fact that the Spurs had fallen short. Again.

The room’s stale aura was indicative of that.

But, instead of hiding in the locker room where only a select few reporters could reach him long after the game’s final whistle, Wembanyama made himself available to the entire room. He fielded questions, answered professionally and left just like any other night. Win or lose.

That’s what made the difference.

“(His) interaction with the media is a bigger thing,” Moubèche said of Wembanyama. “He was never talking in France. You know, he went from maybe two press conferences a year to something like 60.”